By the end of the 1970s, Prof. Gagin and his work had become of interest to me. After all, as I learned in Durango, nothing could be taken at face value in the cloud seeding literature unless I had personally validated that literature by scrutinizing every detail of the published claims in it, looking for omissions and exaggerated claims, something reviewers of manuscripts certainly did NOT do.

I had a lot of experience by this time. I had reanalyzed the previous published reports of cloud seeding successes in the Wolf Creek Pass experiment (Rangno 1979, J. Appl. Meteor.); the Skagit Project (Hobbs and Rangno 19781, J. Appl. Meteor.), and had authored comments critical of the published foundations of the Climax and Wolf Creek Pass experiments in Colorado (Hobbs and Rangno1 1979, J. Appl. Meteor.) and others.

What was to transpire was that the person Joanne Malkus Simpson suggested to give up meteorology, me, helped eliminate the reasons why anyone, let alone her, would continue to believe that “statues” should be raised to honor Prof. A. Gagin’s contributions to cloud seeding. Here’s what happened.

The Israel chapter of my cloud seeding life begins

In about 1979, the Director of my group at the University of Washington, Prof. Peter V. Hobbs, challenged me to look into the Israeli cloud seeding experiments: “if you really want to have an impact, you should look into the Israeli experiments.” I guess he thought I had a knack seeing through mirages of cloud seeding successes.

I did begin to look at them at that time. Prof. Hobbs asked me to prepare a list of the questions I had come up with after I started reading the literature about the Israeli experiments. He wanted to ask questions of Prof. Gagin at the latter’s talk at the 1980 Clermont-Ferrand International Weather Modification conference in France. Those at the conference said that he did ask Prof. Gagin questions but it wouldn’t have been like Prof. Hobbs, as I began to learn over the years in his group, to have said, “My staff member has some questions for you, Abe.” Maybe he thought that wasn’t important.

I already knew something of the rain climate of Israel long before reading about the Israeli cloud seeding experiments. This was due to a climate paper I was working on when I arrived in Durango, CO, as a potential master’s thesis for SJS. My study was about “decadal” rainfall shifts in central and southern California and I wanted to know if what I observed in California had also been observed in Israel, a country with long term, high quality rainfall records and one having a Mediterranean climate like California. I received several publications from the Foreign Data Collections group at the National Climatic Center in those days, such as Dove Rosnan’s 1955 publication, “100 years of Rainfall at Jerusalem.”

So, I was not coming into the Israel cloud seeding literature “blind” to its surprisingly copious winter rain climate. Jerusalem averages about 24 inches of rain between October and May, something akin to San Francisco despite being much farther south than SFO.

My interest in the Israeli cloud seeding experiments, however, ebbed and flowed in a hobby fashion until the summer of 1983 when I decided to plot some balloon soundings when rain was falling, or had fallen within the hour, at Bet Dagan, Israel, and Beirut, Lebanon, balloon launch sites. Anyone could have done this.

The plots were stunning!

Dashed line is the pseudoadiabatic lapse rate; solid line, the adiabatic lapse rate. The synoptic station data are those at the launch time or within 90 min.

Rain was clearly falling from clouds with much warmer tops at both sites than was being indicated in the descriptions of the clouds necessary for rain formation in Israel by Prof. Gagin, descriptions that made them look plump with seeding potential. His descriptions were of clouds having to be much deeper, 1-2 km, before they formed rain. And those descriptions were key in supporting statistical cloud seeding results that gave the first two experiments, referred to as Israel-1 and Israel-2, so much credibility in the scientific community (Kerr 19821, Science magazine). The deeper clouds described meant that there was a load of water in the upper parts of the clouds that wasn’t coming out as rain.

Shallower clouds that were raining meant that there wasn’t going to be so much water in deeper clouds that could be tapped by cloud seeding; much of it would have fallen out as rain before they reached the heights thought to be needed for cloud seeding.

I also scrutinized Prof. Gagin’s airborne Cumulus cloud reports that appeared in the early and mid-1970s. I found several anomalies in them when compared to other Cumulus cloud studies and our own measurements of Cumulus clouds. One example:

While the 3rd quartile droplets became larger above cloud base as expected, droplets >24 um diameter were nil until suddenly increasing above the riming-splintering temperature zone of -3° to -8°C. Those larger drops should have increased in a nearly linearly way as did the 3rd quartile drop diameters. If appreciable concentrations of >24 um diameter droplets had been reported in this temperature zone, cloud experts would have deemed them ripe for an explosion of natural ice, not for cloud seeding. So this odd graph left questions.

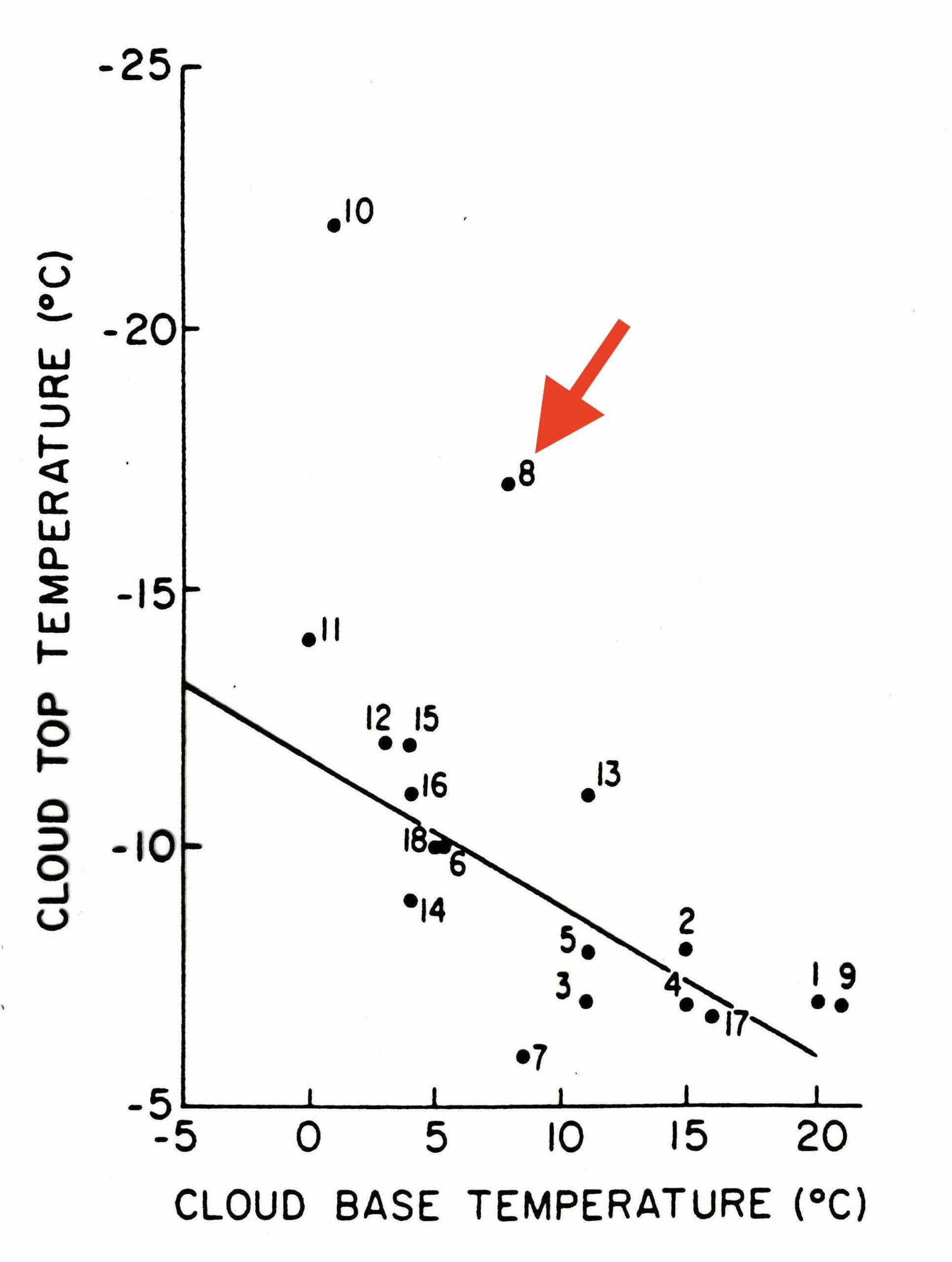

Too, the temperature at which ice first appeared in Israeli clouds, according to Prof. Gagin’s reports, was much lower than similar clouds as seen by data point 8 in the figure below constructed in 1984 (published in 1988, Rangno and Hobbs, Atmos. Res.)

When I read about how seeding was carried out in the first experiment, Israel-1, I learned to my astonishment that only about 70 h of seeding was done during whole winter seasons upwind of each of the two targets by a single aircraft. I concluded that there could not possibly have been a statistically significant effect on rainfall from seeding clouds given the true precipitating nature of Israeli clouds, the number of days with showers, and the small amount of seeding carried out. In Israel-2, the experimenters added a second aircraft and 42 ground cloud seeding generators (NAS 1973). They, too, must have realized they hadn’t seeded enough in Israel-1, I though.

Another red flag jumped out in the first peer-reviewed paper that evaluated Israel-1 by Wurtele (1971, J. Appl. Meteor.), She found that the greatest statistical significance in Israel-1 was not in either one of the “cross-over” targets, but in the Buffer Zone (BZ) between them that the seeding aircraft was told to avoid. This BZ anomaly had occurred on days when southernmost target was being seeded. In her paper, Wurtele quoted the chief meteorologist of Israel-1, Mr. Karl Rosner, who stated that the high statistical significance in the BZ could hardly have been produced by inadvertent cloud seeding by the single aircraft that flew seeding missions.

The original experimenters, Gagin and Neumann (1974) addressed this statistical anomaly in the BZ but did attribute it to cloud seeding based on their own wind analysis.

A Hasty 1983 Submission

Armed with all these findings, I decided to see how fast I could write up my findings and submit them to the J. Appl. Meteor.; I came into the University of Washington on July 4th, 1983, and wrote the entire manuscript that day. I submitted it to the J. Appl. Meteor. the next day. (Prof. Hobbs was on sabbatical in Europe at this time.)

I was sure it would be accepted, though likely with revisions required. No reviewer could not see, I thought, that there was a problem with the existing published cloud reports from Israel.

My conclusions were against everything that had been written about those experiments at that time, that the clouds were not ripe for cloud seeding, but the opposite of “ripe” for that purpose.

In retrospect, it wasn’t surprising that I was informed six months later that my manuscript was rejected by three of four reviewers: “Too much contrary evidence. You can’t be right” was the general tone of the message.

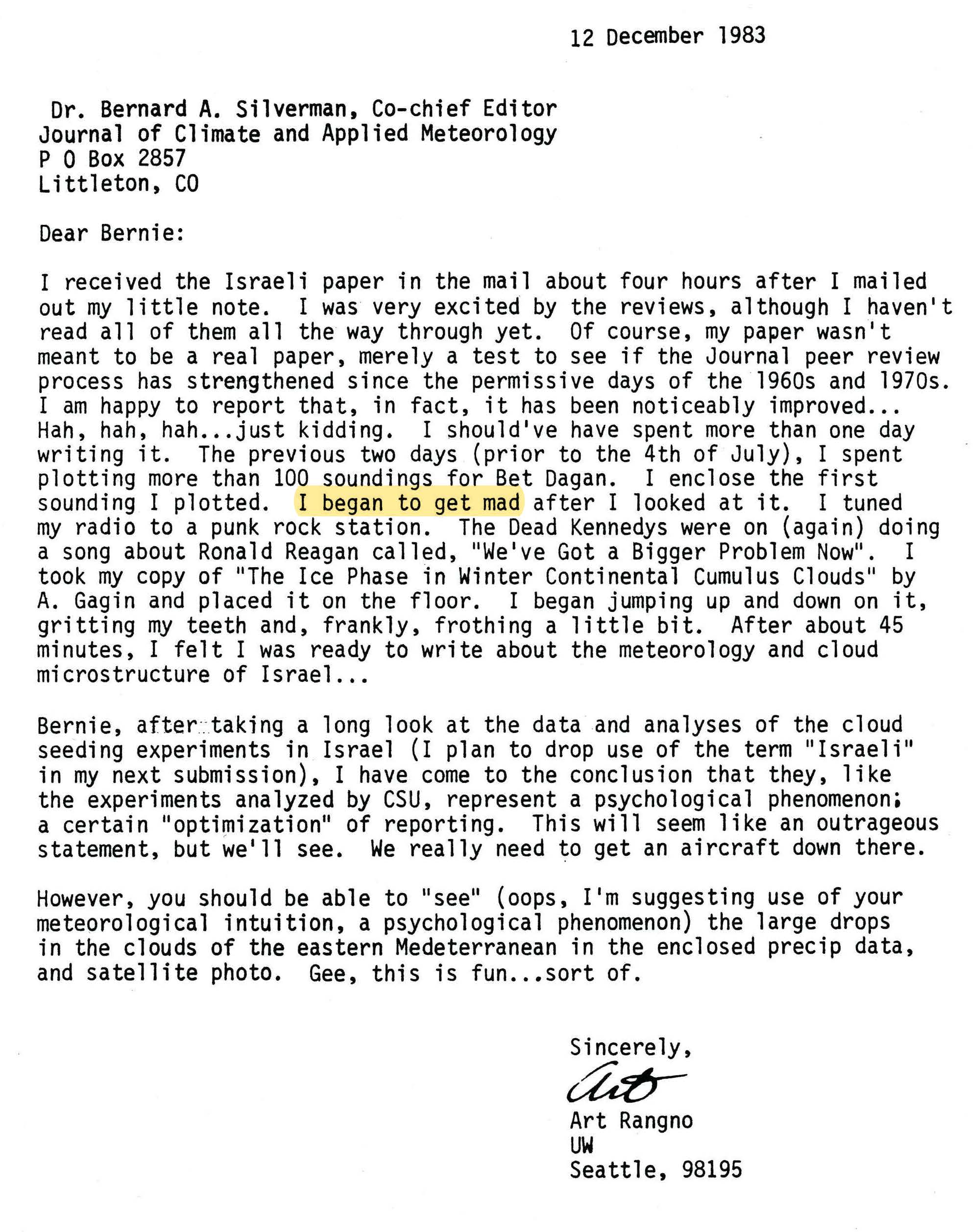

Nevertheless, I was surprised by the rejection, thinking my evidence was too strong for an outright rejection. I tried to make the best of it in a humorous way to the journal editor, Dr. Bernard A. Silverman, passed the news along. I hope you, the reader, if any, smile when you read this:

In 1984 at the Park City, UT, Weather Modification Conference, I had my first personal interaction with Prof. Gagin. I was giving an invited talk with an assigned title at that conference about the wintertime clouds of the Rockies, “How Good Are Our Conceptual Models of Orographic Cloud Seeding?”

Prof. Gagin informed me that he had been one of the four reviewers of my 1983 rejected manuscript. He “lectured” me sternly between conference presentations about how wrong I was about his published descriptions of Israeli clouds that had a hard time raining naturally until they got deep and cold at the top.

Rejection and Lecture Have No Effect

The rejection of my 1983 paper and Prof. Gagin’s “lecture” about how wrong I was about Israeli clouds, however, had no effect whatsoever on what I thought about them.

I felt I could interpret balloon soundings just fine after the hundreds and hundreds I examined in Durango with the CRBPP while looking out the window to see what those soundings were depicting. I marveled, instead, that reviewers couldn’t detect the obvious, especially Dr. Bernard A. Silverman, the Editor of the J. Appl. Meteor.

After that rejection that moved on to studies of secondary ice formation in clouds in Peter Hobbs group, published in Hobbs and Rangno 1985, J. Atmos. Sci.), but the thought of going to Israel began to surface. Someone has to do something!

It was about this time that I read about American physicist, R. W. Wood, going to France to expose what he believed to be the delusion of N-Ray radiation reported by Prosper René Blondlot (Broad and Wade 1982, Betrayers of the Truth). I thought, “I bet I could do that same kind of thing,” thinking that Prof. Gagin might well be similarly deluded about his clouds.

A Resignation Followed by the Cloud Investigation Trip to Israel

And so, following the historical precedent that R. W. Wood set, I hopped on a plane to Israel at the beginning of January 1986 following my resignation from Prof. Hobbs’ Cloud and Aerosol Research Group.

Resigning from the Job I Loved .

My resignation was in protest over issues of credit here and there that had been building up for nearly a decade in Peter Hobbs group2. Peter had lost several good researchers over this same issue. In a late December 1985 meeting with Prof. Hobbs prior to my January 1986 trip, he described me as “arrogant” for thinking I knew more about the clouds of Israel than those who studied them “in their own backyard.”

“Confident” would have been more appropriate than the word, “arrogant” Prof. Hobbs had used. I smirked when he said that; I couldn’t help myself. I had done my homework in the process of writing that short paper in 1983 critical of those cloud reports when Peter was on sabbatical. In fact, I was so confident about my assessment of Israeli clouds that I told Prof. Peter Hobbs, Prof. Robert G. Fleagle (also with the University of Washington) and Roscoe R. Braham, Jr.3, North Carolina State University, and others, that I was about “80 % sure” of my assessment of Israeli clouds from 7,000 miles away even before I went.

My Agenda

It was true, however, that I wanted to show the world by going to Israel that I was the best at “outing” mistaken or fraudulent cloud and or cloud seeding reports, ones that were considered credible by the entire scientific community, including Prof. Hobbs4. However, virtually any low-level forecasting meteorologist could do what I did, especially storm chasing types like me, that was the fun of it.

And, here was a chance to do something that would be considered, “historic,” just like Wood’s trip to France was!

Another intriguing factor contributing to the idea of going to Israel was the statement expressed by Peter Hobbs to me a few years earlier; “No one’s been able to get a plane in there.” He told me that British meteorologist and cloud physics expert, Sir B. J. Mason, had said the same thing to him. I wasn’t a plane, but by god, I was going to “get in there.” The view of Prof. Hobbs and Sir B. J. Mason was later to be confirmed in a letter to me in Israel by Prof. Gabor Vali, University of Wyoming cloud researcher who wrote of six attempts to do airborne research of Israeli clouds, all denied.

Too, I looked forward to going to Israel and seeing what that country was like, too, with all of its biblical history.

And, if it was a case of delusion, as American physicist, R. W. Wood, encountered with the N-Ray episode, Prof. Gagin would be happy to cooperate with me and let me see radar tops of precipitating clouds. Prosper-René Blondlot had cooperated with Dr. Wood, allowing him to watch an N-Ray experiment.

But if Prof. Gagin didn’t cooperate with me, I could just hop on the next plane back to America. I would “know” I was right about those clouds without even seeing them!

=============

1Corrections to Kerr’s 1982 Science article were published by Prof. Hobbs in Science in October 1982. In the original article, Prof. Hobbs inadvertently led Kerr to believe that he himself, and not me, had conducted the reanalysis and other work that undermined the Climax cloud seeding experiments. Prof. Hobbs apologized to me as soon as he saw Kerr’s article. Still…..

2Authorship sequences on publications under Prof. Hobbs’ stewardship sometimes did not represent the progenitor of a work; i.e., that person who should be first author; the person who originated the research, wrote the drafts describing results, the person who had done all the analysis that went into it, as in these footnoted cases of authorship where Prof. Hobbs had placed himself as lead author. Prof. Hobbs was a wonderful science editor and made great improvements to drafts that he received. The authorship sequence problem was to mostly go away after I resigned.

3My resignation letter was 27 single spaced pages!

4Prof. Braham kept the letters I wrote to him and they can be found in his archive at North Carolina State University.

5See Prof. Hobbs 1975 “Personal Viewpoint” comment in Sax et al. 1975, J. Appl. Meteor., “Where Are We Now and Where Should We Be Going?” weather modification review.